# Coordinates {#sec-cs}

"_Data are not just numbers, they are numbers with a context_";

"_In data analysis, context provides meaning_" [@cobbmoore]

Before we can try to understand geometries like points, lines,

polygons, coverage and grids, it is useful to review coordinate

systems so that we have an idea what exactly coordinates of a

point reflect. For spatial data, the location of observations

are characterised by coordinates, and coordinates are defined in

a coordinate system. Different coordinate systems can be used for

this, and the most important difference is whether coordinates are

defined over a 2 dimensional or 3 dimensional space referenced

to orthogonal axes (Cartesian coordinates), or using distance

and directions (polar coordinates, spherical and ellipsoidal

coordinates). Besides a location of observation, all observations

are associated with time of observation, and so time coordinate

systems are also briefly discussed. First we will briefly review

_quantities_, to learn what units and datum are.

## Quantities, units, datum {#sec-units}

\index{quantities}

\index{units}

\index{measurement units}

The VIM ("International Vocabulary of Metrology", @vim)

defines a _quantity_ as a "property of a phenomenon, body, or

substance, where the property has a magnitude that can be expressed

as a number and a reference", where "[a] reference can be a measurement

unit, a measurement procedure, a reference material, or a combination

of such." Although one could argue about whether all data is

constituted of quantities, there is no need to argue that proper

data handling requires that numbers (or symbols) are accompanied

by information on what they mean, in particular what they refer to.

A measurement system consists of _base units_ for base quantities, and

_derived units_ for derived quantities. For instance, the SI system

of units [@SI] consists of seven base units: length (metre,

m), mass (kilogram, kg), time (second, s), electric current

(ampere, A), thermodynamic temperature (Kelvin, K), amount of

substance (mole, mol), and luminous intensity (candela, cd).

Derived units are composed of products of integer powers of base

units; examples are speed ($\mbox{m}~\mbox{s}^{-1}$), density

($\mbox{kg}~\mbox{m}^{-3}$) and area ($\mbox{m}^2$).

The special case of unitless measures can refer to either cases

where units cancel out (for instance mass fraction: kg/kg, or angle measured

in rad: m/m) or to cases where objects or events were counted

(such as "5 apples"). Adding an angle to a count of apples would not

make sense; adding 5 apples to 3 oranges may make sense if the

result is reinterpreted in terms of a superclass, in this case as _pieces of fruit_.

Many data variables have units that are not expressible as SI base

units or derived units. @hand discusses many such measurement scales,

including those used to measure variables like intelligence in

social sciences, in the context of measurement units.

For many quantities, the natural origin of values is zero. This

works for amounts, where differences between amounts result in

meaningful negative values. For locations and times, differences

have a natural zero interpretation: distance and duration. Absolute

location (position) and time need a fixed origin, from which we

can meaningfully measure other absolute space time points: we

call this **a datum**.

For space, a datum involves more than one dimension. The combination

of a datum and a measurement unit (scale) is a _reference system_.

\index{datum}

We will now elaborate how spatial locations can be expressed as

either ellipsoidal or Cartesian coordinates. The next sections will

deal with temporal and spatial reference systems, and how they are

handled in R.

## Ellipsoidal coordinates

```{r fig-polar, echo=!knitr::is_latex_output() }

#| out.width: 60%

#| fig.cap: "Two-dimensional polar (red) and Cartesian (blue) coordinates"

#| code-fold: true

par(mar = rep(0,4))

plot(3, 4, xlim = c(-6,6), ylim = c(-6,6), asp = 1)

axis(1, pos = 0, at = 0:6)

axis(2, pos = 0, at = -6:6)

xd <- seq(-5, 5, by = .1)

lines(xd, sqrt(25 - xd^2), col = 'grey')

lines(xd, -sqrt(25 - xd^2), col = 'grey')

arrows(0, 0, 3, 4, col = 'red', length = .15, angle = 20)

text(1.5, 2.7, label = "r", col = 'red')

xd <- seq(3/5, 1, by = .1)

lines(xd, sqrt(1 - xd^2), col = 'red')

text(1.2, 0.5, label = parse(text = "phi"), col = 'red')

lines(c(3,3), c(0,4), lty = 2, col = 'blue')

lines(c(0,3), c(4,4), lty = 2, col = 'blue')

text(3.3, 0.3, label = "x", col = 'blue')

text(0.3, 4.3, label = "y", col = 'blue')

```

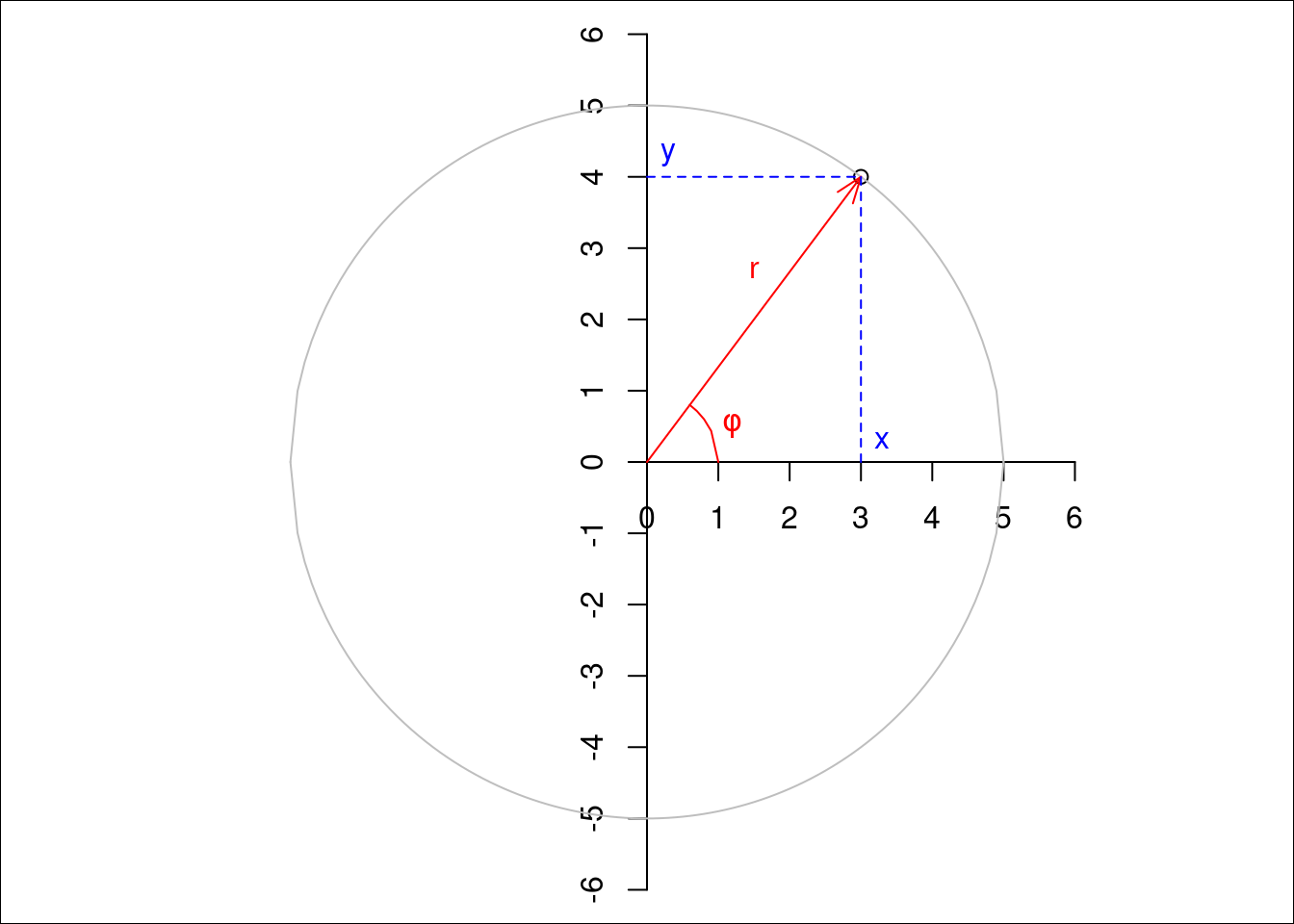

@fig-polar shows both polar and Cartesian coordinates

for a two-dimensional situation. In Cartesian coordinates,

the point shown is $(x,y) = (3,4)$, for polar coordinates it is

$(r,\phi) = (5, \mbox{arctan}(4/3))$, where $\mbox{arctan}(4/3)$ is

approximately $0.93$ radians, or $53^{\circ}$. Note that $x$, $y$

and $r$ all have length units, where $\phi$ is an angle (a unitless

length/length ratio). Converting back and forth between Cartesian

and polar coordinates is trivial, as

$$x = r~\mbox{cos} \phi,\ \ \ y = r~\mbox{sin} \phi, \ \mbox{and}$$

$$r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}, \ \ \ \phi = \mbox{atan2}(y, x)$$

where $\mbox{atan2}$ is used in favour of $\mbox{atan}(y/x)$ to take care

of the right quadrant.

### Spherical or ellipsoidal coordinates

\index{ellipsoidal coordinates}

\index{coordinates!ellipsoidal}

\index{coordinates!geocentric}

\index{coordinates!Cartesian}

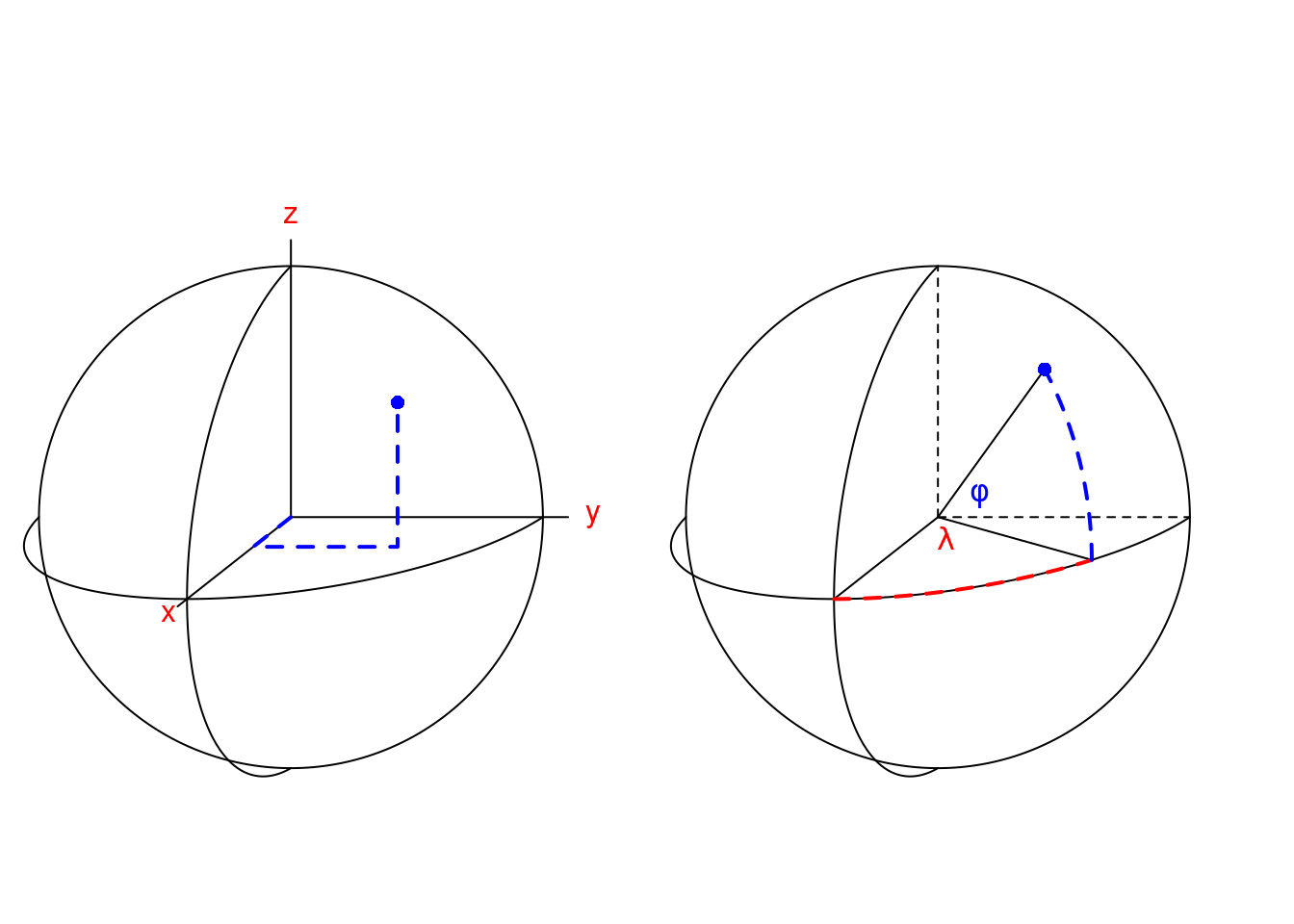

In three dimensions, where Cartesian coordinates are expressed as

$(x,y,z)$, spherical coordinates are the three-dimensional equivalent

of polar coordinates and can be expressed as $(r,\lambda,\phi)$, where:

* $r$ is the radius of the sphere,

* $\lambda$ is the longitude, measured in the $(x,y)$ plane counter-clockwise from positive $x$, and

* $\phi$ is the latitude, the angle between the vector and the $(x,y)$ plane.

@fig-sphere illustrates Cartesian geocentric and

ellipsoidal coordinates.

```{r fig-sphere, echo=!knitr::is_latex_output()}

#| fig.cap: "Cartesian geocentric coordinates (left) measure three distances, ellipsoidal coordinates (right) measure two angles, and possibly an ellipsoidal height"

#| code-fold: true

library(sf) |> suppressPackageStartupMessages()

e <- cbind(-90:90,0) # equator

f1 <- rbind(cbind(0, -90:90)) # 0/antimerid.

f2 <- rbind(cbind(90, -90:90), cbind(270, 90:-90))# +/- 90

eq <- st_sfc(st_linestring(e), st_linestring(f1), st_linestring(f2), crs='OGC:CRS84')

geoc <- st_transform(eq, "+proj=geocent")

cc <- rbind(geoc[[1]], NA, geoc[[2]], NA, geoc[[3]])

from3d <- function(x, offset, maxz, minz) {

x = x[,c(2,3,1)] + offset # move to y right, x up, z backw

x[,2] = x[,2] - maxz # shift y to left

d = maxz

z = x[,3] - minz + offset

x[,1] = x[,1] * (d/z)

x[,2] = x[,2] * (d/z)

x[,1:2]

}

maxz <- max(cc[,3], na.rm = TRUE)

minz <- min(cc[,3], na.rm = TRUE)

offset <- 3e7

circ <- from3d(cc, offset, maxz, minz)

mx <- max(cc, na.rm = TRUE) * 1.1

x <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(mx, 0, 0))

y <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(0, mx, 0))

z <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(0, 0, mx))

ll <- rbind(x, NA, y, NA, z)

l0 <- from3d(ll, offset, maxz, minz)

mx <- max(cc, na.rm = TRUE) * 1.2

x <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(mx, 0, 0))

y <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(0, mx, 0))

z <- rbind(c(0, 0, 0), c(0, 0, mx))

ll <- rbind(x, NA, y, NA, z)

l <- from3d(ll, offset, maxz, minz)

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

par(mar = rep(0,4))

plot.new()

plot.window(xlim = c(min(circ[,1],na.rm = TRUE), 3607103*1.02),

ylim = c(min(circ[,2],na.rm = TRUE), 2873898*1.1), asp = 1)

lines(circ)

lines(l0)

text(l[c(2,5,8),], labels = c("x", "y", "z"), col = 'red')

# add POINT(60 47)

p <- st_as_sfc("POINT(60 47)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p <- p[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p[1],0,0), c(p[1],p[2],0), c(p[1],p[2],p[2]))

ptsl <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(ptsl, col = 'blue', lty = 2, lwd = 2)

points(ptsl[4,1], ptsl[4,2], col = 'blue', cex = 1, pch = 16)

plot.new()

plot.window(xlim = c(min(circ[,1],na.rm = TRUE), 3607103*1.02),

ylim = c(min(circ[,2],na.rm = TRUE), 2873898*1.1), asp = 1)

lines(circ)

p <- st_as_sfc("POINT(60 47)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p <- p[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p[1],p[2],p[3]))

pt <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(pt)

points(pt[2,1], pt[2,2], col = 'blue', cex = 1, pch = 16)

p0 <- st_as_sfc("POINT(60 0)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p0 <- p0[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p0[1],p0[2],p0[3]))

pt <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(pt)

p0 <- st_as_sfc("POINT(0 0)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p0 <- p0[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p0[1],p0[2],p0[3]))

pt <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(pt)

p0 <- st_as_sfc("POINT(0 90)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p0 <- p0[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p0[1],p0[2],p0[3]))

pt <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(pt, lty = 2)

p0 <- st_as_sfc("POINT(90 0)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p0 <- p0[[1]]

pts <- rbind(c(0,0,0), c(p0[1],p0[2],p0[3]))

pt <- from3d(pts, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(pt, lty = 2)

f1 <- rbind(cbind(0:60, 0))

arc <- st_sfc(st_linestring(f1), crs='OGC:CRS84')

geoc <- st_transform(arc, "+proj=geocent")

cc <- rbind(geoc[[1]])

circ <- from3d(cc, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(circ, col = 'red', lwd = 2, lty = 2)

f1 <- rbind(cbind(60, 0:47))

arc <- st_sfc(st_linestring(f1), crs='OGC:CRS84')

geoc <- st_transform(arc, "+proj=geocent")

cc <- rbind(geoc[[1]])

circ <- from3d(cc, offset, maxz, minz)

lines(circ, col = 'blue', lwd = 2, lty = 2)

text(pt[1,1]+100000, pt[1,2]+50000, labels = expression(phi), col = 'blue') # lat

text(pt[1,1]+20000, pt[1,2]-50000, labels = expression(lambda), col = 'red') # lng

```

$\lambda$ typically varies between $-180^{\circ}$ and $180^{\circ}$

(or alternatively from $0^{\circ}$ to $360^{\circ}$), $\phi$ from

$-90^{\circ}$ to $90^{\circ}$. When we are only interested in points

_on_ a sphere with given radius, we can drop $r$: $(\lambda,\phi)$

now suffice to identify any point.

\newpage

It should be noted that this is just _a_ definition, one could for

instance also choose to measure polar angle, the angle between

the vector and $z$, instead of latitude. There is also a long

tradition of specifying points as $(\phi,\lambda)$ but throughout

this book we will stick to longitude-latitude, $(\lambda,\phi)$.

The point denoted in @fig-sphere has $(\lambda,\phi)$ or ellipsoidal

coordinates with angular values

```{r echo=!knitr::is_latex_output()}

#| code-fold: true

#| collapse: false

p <- st_as_sfc("POINT(60 47)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84')

p[[1]]

```

measured in degrees, and geocentric coordinates

```{r echo=!knitr::is_latex_output()}

#| code-fold: true

#| collapse: false

p <- st_as_sfc("POINT(60 47)", crs = 'OGC:CRS84') |> st_transform("+proj=geocent")

p[[1]]

```

measured in metres.

\index{coordinates!units}

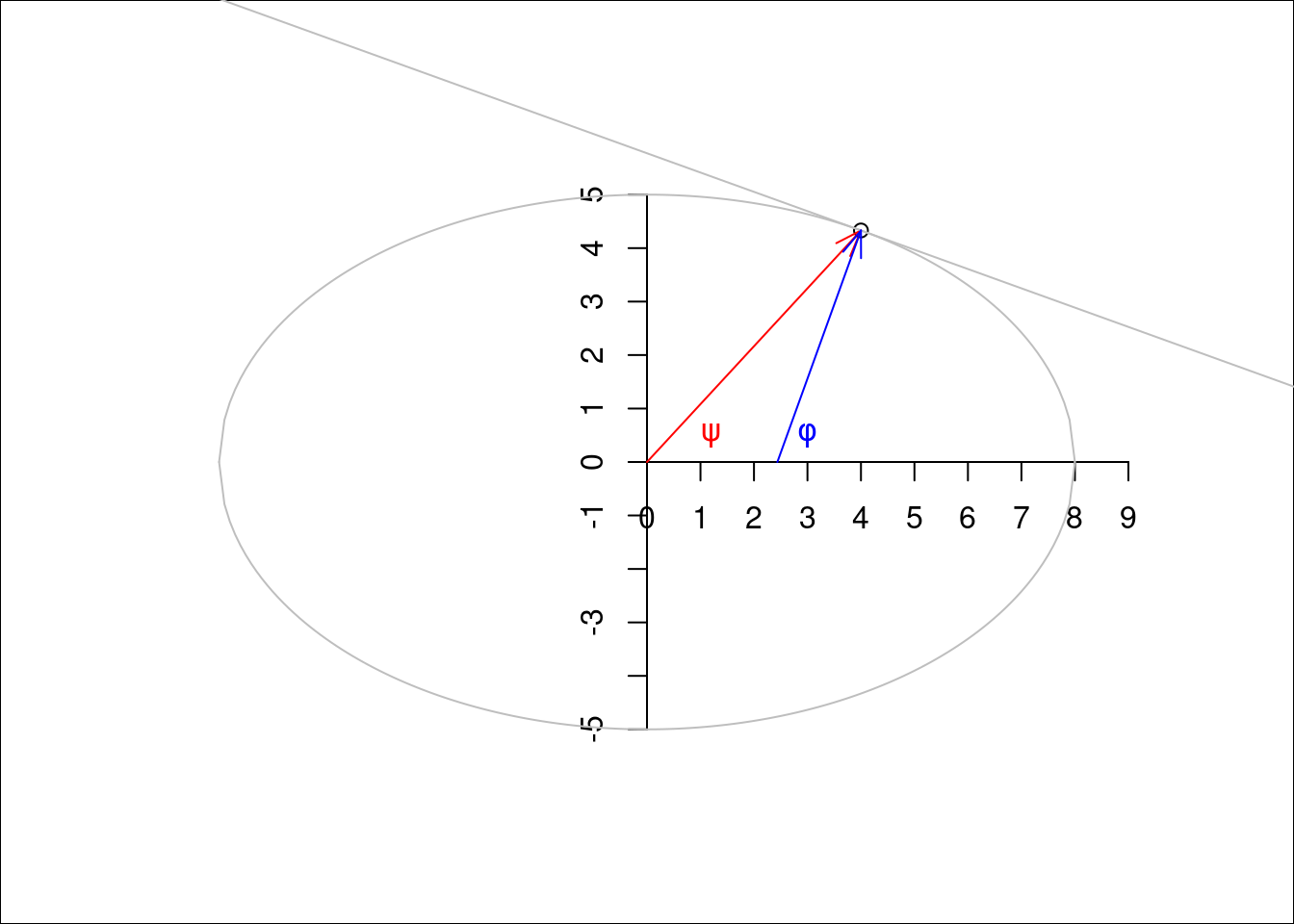

For points on an ellipse, there are two ways in which angle can be

expressed (@fig-ellipse): measured from the centre of the ellipse

($\psi$), or measured perpendicular to the tangent on the ellipse

at the target point ($\phi$).

```{r fig-ellipse, echo=!knitr::is_latex_output() }

#| out.width: 60%

#| fig.cap: "Angles on an ellipse: geodetic (blue) and geocentric (red) latitude"

#| code-fold: true

par(mar = rep(0,4))

x <- 4

y <- 5/8 * sqrt(48)

plot(x, y, xlim = c(-6,6), ylim = c(-8,8), asp = 1)

axis(1, pos = 0, at = 0:9)

axis(2, pos = 0, at = -5:5)

xd <- seq(-8, 8, by = .1)

lines(xd, 5/8 * sqrt(64 - xd^2), col = 'grey')

lines(xd, 5/8 * -sqrt(64 - xd^2), col = 'grey')

arrows(0, 0, x, y, col = 'red', length = .15, angle = 20)

b <- (x * 25) / (-y * 64)

a <- y - x * b

abline(a, b, col = 'grey')

b <- -1/b

x0 <- x - y / b

arrows(x0, 0, x, y, col = 'blue', length = .15, angle = 20)

text(1.2, 0.5, label = parse(text = "psi"), col = 'red')

text(3, 0.5, label = parse(text = "phi"), col = 'blue')

```

The most commonly used parametric model for the Earth is _an

ellipsoid of revolution_, an ellipsoid with two equal semi-axes

[@iliffelott]. In effect, this is a flattened sphere (or spheroid):

the distance between the poles is (slightly: about 0.33%) smaller

than the distance between two opposite points on the equator. Under

this model, longitude is always measured along a circle (as in

@fig-sphere), and latitude along an ellipse (as in

@fig-ellipse). If we

think of @fig-ellipse as a cross section of the Earth

passing through the poles, the _geodetic_ latitude measure $\phi$

is the one used when no further specification is given. The latitude

measure $\psi$ is called the _geocentric latitude_.

\index{latitude!geodetic}

\index{latitude!geocentric}

\index{longitude}

\index{ellipsoid of revolution}

\index{altitude}

\index{altitude!direction}

\index{coordinates!altitude}

we can add _altitude_ or elevation to longitude and latitude to

define points that are above or below the ellipsoid, and obtain

a three-dimensional space again. When defining altitude, we need

to choose:

* where zero altitude is: on the ellipsoid, or relative to the surface approximating mean sea level (the geoid)?

* which direction is positive, and

* which direction is "straight up": perpendicular to the ellipsoid surface,

or in the direction of gravity, perpendicular to the surface of the geoid?

All these choices may matter, depending on the application area

and required measurement accuracies.

The shape of the Earth is not a perfect ellipsoid. As a consequence,

several ellipsoids with different shape parameters and bound to

the Earth in different ways are being used. Such ellipsoids are called

_datums_, and are briefly discussed in @sec-crs, along

with _coordinate reference systems_.

### Projected coordinates, distances {#sec-projections}

Because paper maps and computer screens are much more abundant

and practical than globes, when we look at spatial

data we see it _projected_: drawn on a flat, two-dimensional

surface. Computing the locations in a two-dimensional space means

that we work with _projected_ coordinates. Projecting ellipsoidal

coordinates means that shapes, directions, areas, or even all three,

are distorted [@iliffelott].

\index{coordinates!projected}

\index{projection}

\index{distance!straight line}

Distances between two points $p_i$ and $p_j$ in Cartesian coordinates are computed

as Euclidean distances, in two dimensions by

$$d_{ij} = \sqrt{(x_i-x_j)^2+(y_i-y_j)^2}$$

with $p_i = (x_i,y_i)$

and in three dimensions by

$$d_{ij} = \sqrt{(x_i-x_j)^2+(y_i-y_j)^2+(z_i-z_j)^2}$$

with $p_i = (x_i,y_i,z_i).$

These distances represent the length of a _straight_ line between

two points $i$ and $j$.

For two points on a circle, the length of the arc of two points $c_1 = (r,{\phi}_1)$ and

$c_2 = (r, \phi_2)$ is

$$s_{ij}=r~|\phi_1-\phi_2| = r ~\theta$$

with $\theta$ the angle between $\phi_1$ and $\phi_2$ in radians.

For very small values of $\theta$, we will have $s_{ij} \approx d_{ij}$,

because a small arc segment is nearly straight.

\index{distance!great circle}

For two points $p_1 = (\lambda_1,\phi_1)$ and $p_2 =

(\lambda_2,\phi_2)$ on a sphere with radius $r'$, the _great circle

distance_ is the arc length between $p_1$ and $p_2$ on the circle

that passes through $p_1$ and $p_2$ and has the centre of the sphere as its centre, and

is given by $s_{12} = r ~ \theta_{12}$ with

$$\theta_{12} = \arccos(\sin \phi_1 \cdot \sin \phi_2 + \cos \phi_1 \cdot \cos \phi_2 \cdot \cos(|\lambda_1-\lambda_2|))$$

the angle between $p_1$ and $p_2$, in radians.

Arc distances between two points on a spheroid are more complicated

to compute; a good discussion on the topic and an explanation of

the method implemented in GeographicLib (part of PROJ) is given

in @karney2013algorithms.

\index{distance!ellipsoidal}

To show that these distance measures actually give different

values, we computed them for the distance Berlin - Paris. Here,

`gc_` refers to ellipsoidal and spherical great circle distances,

`str_` refers to straight line, Euclidean distances between

Cartesian geocentric coordinates associated on the WGS84 ellipse

and sphere:

```{r echo=!knitr::is_latex_output(), message=FALSE}

#| code-fold: true

#| collapse: false

pts <- st_sfc(st_point(c(13.4050, 52.5200)), st_point(c(2.3522, 48.8566)), crs = 'OGC:CRS84')

s2_orig <- sf_use_s2(FALSE)

d1 <- c(gc_ellipse = st_distance(pts)[1,2])

sf_use_s2(TRUE)

# or, without using s2, use st_distance(st_transform(pts, "+proj=cart +ellps=sphere"))

d2 <- c(gc_sphere = st_distance(pts)[1,2])

p <- st_transform(pts, "+proj=cart +ellps=WGS84")

d3 <- c(str_ellipse = units::set_units(sqrt(sum(apply(do.call(cbind, p), 1, diff)^2)), m))

p2 <- st_transform(pts, "+proj=cart +ellps=sphere")

d4 <- c(str_sphere = units::set_units(sqrt(sum(apply(do.call(cbind, p2), 1, diff)^2)), m))

res <- c(d1, d3, d2, d4) # note order

# print as km, re-add names:

sf_use_s2(s2_orig) # back to what it was before changing

res |> units::set_units(km) |> setNames(names(res)) |> print(digits = 5)

```

### Bounded and unbounded spaces {#sec-bounded}

\index{sphere}

\index{space!bounded}

\index{space!unbounded}

Two-dimensional and three-dimensional Euclidean spaces ($R^2$ and

$R^3$) are unbounded. Every line in this space has infinite length,

and areas or volumes have no natural upper limit. In contrast,

spaces defined on a circle ($S^1$) or sphere ($S^2$) define a bounded

set: there may be infinitely many points but the length and area

of the circle, and the radius, area and volume of a sphere are bounded.

This may sound trivial but leads to some interesting challenges

when handling spatial data. A polygon on $R^2$ has unambiguously an

inside and an outside. On a sphere, $S^2$, any polygon divides

the sphere in two parts, and which of these two is to be considered

inside and which outside is ambiguous and needs to be defined

by the traversal direction. @sec-spherical will further discuss

consequences when working with geometries on $S^2$.

\index{polygon!on the sphere}

\index{polygon!inside, outside}

## Coordinate reference systems {#sec-crs}

\index{coordinate reference systems}

We follow @lott2015 when defining the following concepts (italics indicate literal quoting):

* a **coordinate system** is a _set of mathematical rules for specifying how coordinates are to be assigned to points_,

* a **datum** is a _parameter or set of parameters that define the position of the origin, the scale, and the orientation of a coordinate system_,

* a **geodetic datum** is a _datum describing the relationship of a two- or three-dimensional coordinate system to the Earth_, and

* a **coordinate reference system** is a _coordinate system that is related to an object by a datum; for geodetic and vertical datums, the object will be the Earth._

\index{coordinate system}

\index{geodetic datum}

A readable text that further explains these concepts is @iliffelott.

The Earth does not follow a regular shape. The topography of the

Earth is of course known to vary strongly, but also the surface

formed by constant gravity at mean sea level, the geoid, is

irregular. A commonly used model that is fit to the geoid is an

ellipsoid of revolution, which is an ellipsoid with two identical

minor axes. Fitting such an ellipsoid to the Earth gives a datum.

However, fitting it to different areas, or based on different sets of

reference points gives different fits, and hence different datums:

a datum can for instance be fixed to a particular tectonic plate

(like the European Terrestrial Reference System 1989 (ETRS89)), others can be globally fit (like WGS84). More local

fits lead to smaller approximation errors.

\index{geoid}

The definitions above imply that coordinates in degrees longitude

and latitude only have a meaning and can only be interpreted

unambiguously as Earth coordinates, when the datum they are

associated with is given.

Note that for projected data, the data that _were_ projected

are associated with a reference ellipsoid (datum). Going from

one projection to another _without_ changing datum is called

_coordinate conversion_, and passes through the ellipsoidal

coordinates associated with the datum involved. This process is

lossless and invertible: the parameters and equations associated

with a _conversion_ are not empirical. Recomputing coordinates in a

new datum is called _coordinate transformation_, and is approximate:

because datums are a result of model fitting, transformations

between datums are models too that have been fit; the equations

involved are empirical, and multiple transformation paths, based

on different model fits and associated with different accuracies,

are possible.

\index{coordinate!conversion}

\index{coordinate!transformation}

Plate tectonics imply that within a global datum, fixed objects may

have coordinates that change over time, and that transformations

from one datum to another may be time-dependent. Earthquakes are a

cause of more local and sudden changes in coordinates. Local datums

may be fixed to tectonic plates (such as ETRS89), or may be dynamic.

\index{datum!dynamic}

## PROJ and mapping accuracy {#sec-projlib}

Very few living people active in open source geospatial software

can remember the time before PROJ. PROJ [@evenden:90] started in the

1970s as a Fortran project, and was released in 1985 as a C library

for cartographic projections. It came with command line tools for

direct and inverse projections, and could be linked to software

to let it support (re)projection directly. Originally, datums were

considered implicit, and no datum transformations were allowed.

\index{PROJ}

\index{PROJ!PROJ.4}

\index{PROJ!proj4string}

In the early 2000s, PROJ was known as PROJ.4, after its never-changing

major version number. Amongst others motivated by the rise of GPS,

the need for datum transformations increased and PROJ.4 was extended

with rudimentary datum support. PROJ definitions for coordinate

reference systems would look like this:

```

+proj=utm +zone=33 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

```

where _key_=_value_ pairs are preceded by a `+` and separated by

a space. This form came to be known as "PROJ.4 string", since the

PROJ project stayed at version 4.x for several decades. Other datums

would come with fields like:

```

+ellps=bessel +towgs84=565.4,50.3,465.6,-0.399,0.344,-1.877,4.072

```

indicating another ellipse, as well as the seven (or three)

parameters for transforming from this ellipse to WGS84 (the "World

Geodetic System 1984" global datum once popularised by GPS),

effectively defining the datum in terms of a transformation to WGS84.

Along with PROJ.4 came a set of databases with known (registered)

projections, from which the best known is the European Petroleum Survey Group (EPSG) registry.

National mapping agencies would provide (and update over time)

their best guesses of `+towgs84` parameters for national coordinate

reference systems, and distribute through the EPSG registry,

which was part of PROJ distributions.

For some transformations, _datum grids_ were available and

distributed as part of PROJ.4: such grids are raster maps that provide

for every location pre-computed values for the shift in longitude

and latitude, or elevation, for a particular datum transformation.

In PROJ.4, every coordinate transformation had to go through a

conversion to and from WGS84; even reprojecting data associated with

a datum different from WGS84 had to go through a transformation to

and from WGS84. The associated errors of up to 100 m were acceptable

for mapping purposes for not too small areas, but some applications

need higher accuracy transformations. Examples include precision

agriculture, planning flights of UAV's, or object tracking.

In 2018, after a successful "GDAL Coordinate System Barn Raising"

initiative, a number of companies profiting from the open source

geospatial software stack supported the development of a more modern,

mature coordinate transformation system in PROJ. Over a few years,

PROJ.4 evolved through versions 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and was hence renamed

into PROJ (or PR$\phi$J).

\index{GDAL!barn raising}

\index{GDAL!datum transformation}

\index{PROJ!datum transformation}

The most notable changes include:

* although PROJ.4 strings can still be used to initialise certain

coordinate reference systems, they are no longer sufficient to

represent all of them; a new format, WKT-2 (described in next section)

replaces it

* WGS84 as a hub datum is dropped: coordinate transformations no longer

need to go through a particular datum

* multiple conversion or transformation paths (so-called pipelines)

to go from CRS A to CRS B are possible, and can be reported along

with the associated accuracy; PROJ will by default use the most accurate

one but user control is possible

* transformation pipelines can chain an arbitrary number of

elementary transformation operations, including swapping of axes

and unit transformations

* datum grids, of which there are now _many_ more, are no longer distributed

with the library but are accessible from a content delivery network (CDN); PROJ allows enabling and

disabling network access to these grids and only downloads the section(s)

of the grid actually needed, storing it in a cache on the user's machine for

future use

* coordinate transformations receive support for epochs, time-dependent

transformations (and hence: four-dimensional coordinates, including the

source and target time)

* the set of files with registered coordinate reference systems is handled

in an SQLite database

* instead of always handling axis order (longitude, latitude),

when the authority defines differently this is now obeyed (but see

@sec-wkt2 and @sec-axisorder)

\index{WKT-2}

\index{PROJ!WKT-2}

\index{projection!accuracy}

All these points sound like massive improvements, and accuracies

of transformation can be below 1 metre. An interesting point

is the last: Where we could safely assume for many decades that

spatial data with ellipsoidal coordinates would have axis order

(longitude, latitude), this is no longer the case. We will see in

@sec-axisorder how to deal with this.

\index{datum!grids}

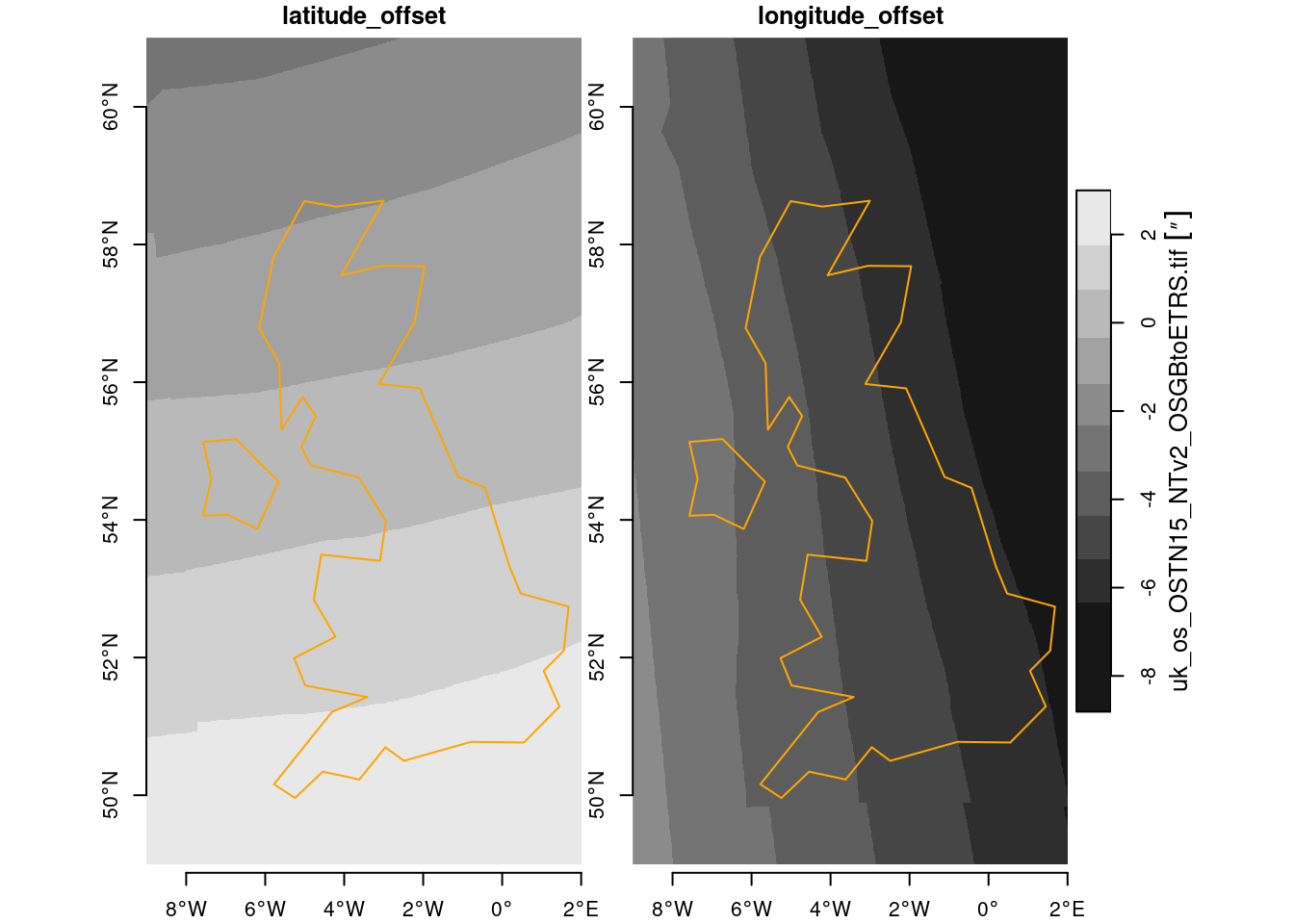

```{r fig-horizontalgrid, echo=!knitr::is_latex_output(), message = FALSE}

#| out.width: 70%

#| fig.cap: "UK horizontal datum grid, from datum OSGB 1936 (EPSG:4277) to datum ETRS89 (EPSG:4258); units arc-seconds"

#| code-fold: true

library(stars)

library(rnaturalearth)

library(dplyr) |> suppressPackageStartupMessages()

countries110 |>

st_as_sf() |>

filter(ADMIN == "United Kingdom") |>

st_geometry() -> uk

filename = "data/uk_os_OSTN15_NTv2_OSGBtoETRS.tif"

r <- if (file.exists(filename)) {

r <- read_stars(filename)

} else {

read_stars("/vsicurl/https://cdn.proj.org/uk_os_OSTN15_NTv2_OSGBtoETRS.tif")

}

hook <- function() {

plot(uk, border = "orange", col = NA, add = TRUE)

}

plot(r[,,,1:2], axes = TRUE, hook = hook, key.pos = 4)

```

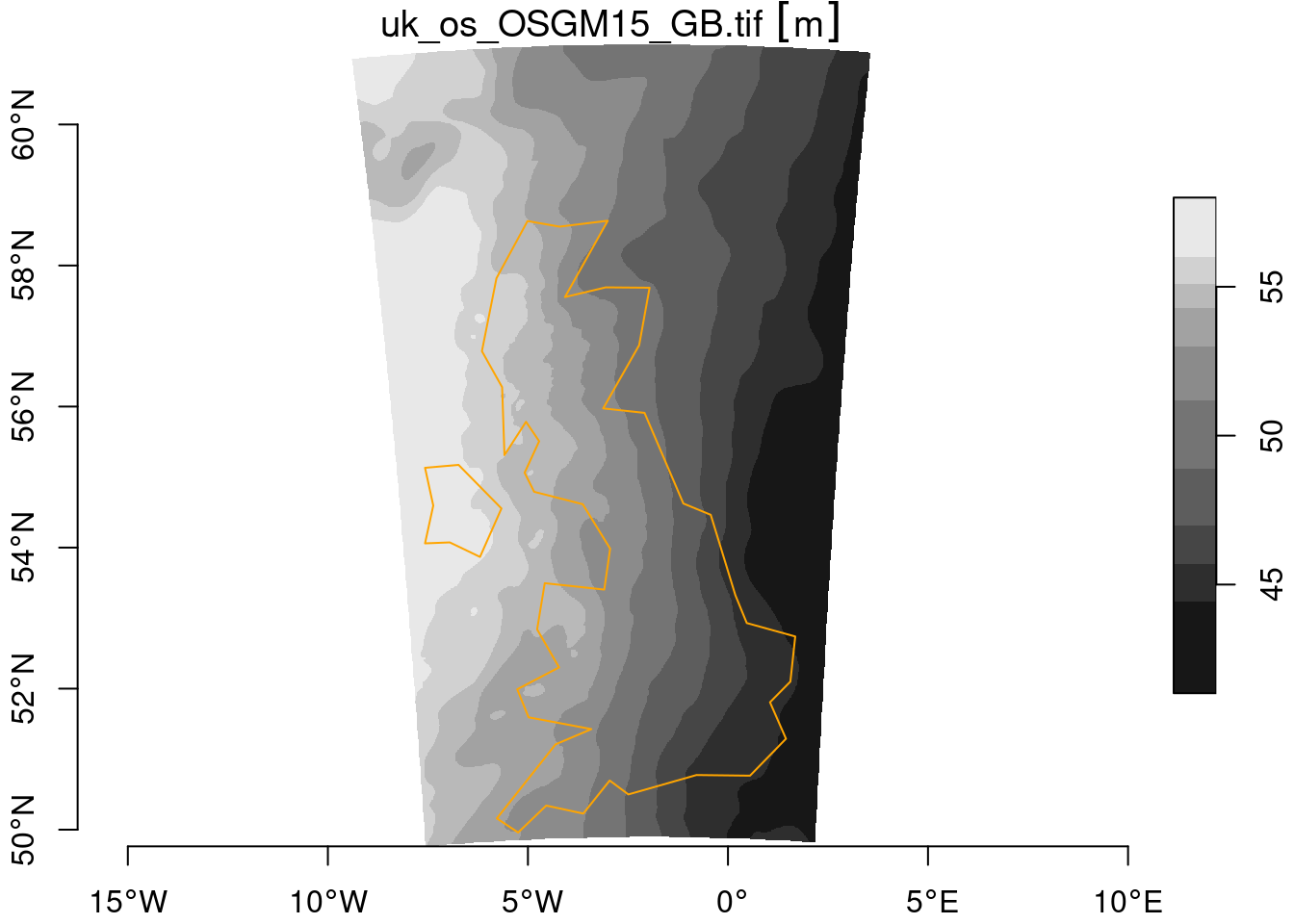

```{r fig-verticalgrid, echo=!knitr::is_latex_output(), message = FALSE}

#| out.width: 70%

#| fig.cap: "UK vertical datum grid, from ETRS89 (EPSG:4937) to ODN height (EPSG:5701), units m"

#| code-fold: true

filename = "data/uk_os_OSGM15_GB.tif"

h <- if (file.exists(filename)) {

read_stars(filename)

} else {

read_stars("/vsicurl/https://cdn.proj.org/uk_os_OSGM15_GB.tif")

}

plot(h, axes = TRUE, reset = FALSE)

plot(uk, border = "orange", col = NA, add = TRUE)

```

\index{coordinates!axis order}

\index{axis order}

Examples of a horizontal datum grids, downloaded from cdn.proj.org,

are shown in @fig-horizontalgrid and for a vertical

datum grid in @fig-verticalgrid. Datum grids may carry

per-pixel accuracy values.

## WKT-2 {#sec-wkt2}

@lott2015 describes a standard for encoding coordinate reference

systems, as well as transformations between them using _well-known text_;

the standard (and format) is referred to informally as

WKT-2. As mentioned above, GDAL and PROJ fully support this encoding.

An example of WKT-2 for CRS `EPSG:4326` is:

\index{coordinates!WKT-2}

\index{WKT-2}

```

GEOGCRS["WGS 84",

ENSEMBLE["World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble",

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (Transit)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G730)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G873)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1150)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1674)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1762)"],

MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G2139)"],

ELLIPSOID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

ENSEMBLEACCURACY[2.0]],

PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

CS[ellipsoidal,2],

AXIS["geodetic latitude (Lat)",north,

ORDER[1],

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

AXIS["geodetic longitude (Lon)",east,

ORDER[2],

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

USAGE[

SCOPE["Horizontal component of 3D system."],

AREA["World."],

BBOX[-90,-180,90,180]],

ID["EPSG",4326]]

```

This shows a coordinate system with the axis order _latitude,

longitude_, although in most practical cases the axis order used is

_longitude, latitude_. The _ensemble_ of WGS84 ellipsoids listed

represents its various updates over time. Ambiguity about _which_

of these ensemble members a particular dataset should use leads to

an uncertainty of several meters. The coordinate reference system

`OGC:CRS84` disambiguates the axis order and explicitly states it

to be `longitude, latitude`, and is the recommended alternative to

WGS84 datasets using this axis order. It does not disambiguate

the datum ensemble problem.

\index{axis order!disambiguate}

\index{WGS84}

\index{OGC:CRS84}

A longer introduction on the history and recent changes in PROJ

is given in @rogerCRS, building upon the work of @knudsen+evers17

and @evers+knudsen17.

## Exercises

Try to solve the following exercises with R (without loading packages); try to use functions where appropriate:

1. list three _geographic_ measures that do not have a natural zero origin

<!-- latitude, longitude, elevation -->

2. convert the $(x,y)$ points $(10,2)$, $(-10,-2)$, $(10,-2)$, and $(0,10)$ to polar coordinates

3. convert the polar $(r,\phi)$ points $(10,45^{\circ})$, $(0,100^{\circ})$, and $(5,359^{\circ})$ to Cartesian coordinates

4. assuming the Earth is a sphere with a radius of 6371 km, compute for $(\lambda,\phi)$ points the great circle distance between $(10,10)$ and $(11,10)$, between $(10,80)$ and $(11,80)$, between $(10,10)$ and $(10,11)$, and between $(10,80)$ and $(10,81)$ (units: degree). What are the distance units?